Against Utopia Issue #4: The Epistemology of Depression Part 4 - The Statistical Gaze: Clinical Trials as the Growth Engine for Prescriptions

Hello, and welcome to Against Utopia, a newsletter that lifts the veil of authoritarian utopianism in science, technology, politics, culture, and medicine, and explores anti-authoritarian alternatives. This is Issue Four, published July 18th, 2018.

In issue 3, I established an understanding of how doctors see. Cognizant of how medical perception develops both historically and culturally, we can now begin to analyze critically how the hegemonic discourse employed by doctors, pharmaceutical marketers, and regulators shapes knowledge of our physiology.

Recall at the end of Issue 3, we discussed some of the typical, patterned ways doctors may have explained medicine to you in the past:

“1 in 5 patients experience improved symptoms on Prozac within 90 days, 1 in 20 experience suicidal thoughts, and 2 out of 5 do not respond. It has a low likelihood of working for you because of other drugs you’re on, so let’s try something else”

How is it that seemingly authoritative statements of medical expertise from doctors have come to take on this wishy-washy, uncertain form? A doctor would think this statistical guesswork something alien, even heretical to the craft of medicine a hundred years ago but now, it seems, fairly common practice.

By 1920, probability and statistics in medical treatment was well understood. However, unlike today, as we saw in issue 3, doctors of that era felt strongly that disease was embodied in subjective experiences that could be extracted with interaction in a medical clinic, that autopsies provided a way to link the pathology of disease with living bodies, and these diseases could be universally and canonically classified.

Somewhere along the way, statistical-inferential expertise like that demonstrated in the example above began to replace statements grounded in physiological and biological functions. The effect appears to many nowadays as if scientist and doctors are hedging all their bets, abandoning medical treatment in favor of medical gambling: “well, if we can’t see into you, and we can’t quite see into your future, perhaps epidemiological numbers will give us a map with which to understand the territory of your body.”

It would be overly reductive of me to ascribe such a complex social, political, and scientific change in diagnostic thinking to a handful of factors. But I do think two factors in the 20th century led us to a situation where our health would no longer be perceived by medical experts as subjectively varied and embodied but rather as something that could be objectified in a spreadsheet and predicted with numbers. These two factors include: 1) the Framingham Heart Study, a landmark epidemiological study that helped us figure out that smoking causes cancer, and led to the creation of the risk factor and 2) the advent and growth of the clinical trial process for drug approval which, as we’ll see, drives most of today’s modern medical research as well as shapes the market for medical diagnosis and pathologization

My aim here is to show how the map of the body created by epidemiological risk factors does not significantly overlap with the territory (human physiology) it is circumscribing, and how as a result, we don’t really seem to cure anything anymore. We’ve just become very good at endlessly identifying disease, and prescribing medication, but we’re no better off in terms of outcomes.

The Framingham Study: “Risk Factors” and Alienation

The landmark Framingham Heart Study began in 1948, involving over 5,000 participants sampled from the small Boston suburb of Framingham, Massachusetts. It carefully followed and monitored this sample for decades, tracking, among many other things, their behaviors (e.g. smoking), their biomarkers (e.g. cholesterol), and any other relevant medical events (heart attacks, deaths). With careful analysis of many data points, it sought to measure the causal connections, if any, between these observed behaviors, recorded biomarkers, and events.

In one of the first publications summarizing its early findings in 1961, Dr. William B. Kannel, the director of the study, introduced the now-common term “risk factor” to refer to the relative probability that a patient with a given condition would develop a certain adverse outcome (i.e. smoking increases the “risk factor” of developing lung-related illness). The term “risk factor” thus became canonized soon after in the medical lexicon. Before this study, doctors believed: atherosclerosis caused heart disease; hypertension was a normal part of aging for everyone; smoking might be related to heart disease; and obesity had no sure bearing on mortality. However, what this study gave researchers was the ability to estimate, with relative statistical certainty, the likelihood that someone who smokes a pack of cigarettes a day will develop lung cancer over the course of their life compared to someone who doesn’t. It became, in other words, very easy to tell a patient how their lifestyle correlated with future outcomes such as obesity, heart disease and cancer. Researchers felt empowered to give causal weight to your actual weight, attributing to your 20 extra pounds an increased likelihood of early death.

Surely, in a vacuum, this might seem like a good thing that doctors and patients could now identify and isolate risk factors for developing disease. No doubt interventions developed to mitigate noted risk factors (e.g. “Quit smoking or you’ll die.”) have done much to reduce the incidence of disease in many patients. In a sense, the Framingham Study offered medicine what it did not have before:the scientific rationale for prescribing preventative interventions.

Unfortunately, these things never happen in a vacuum. They occur in the hegemonic domain of the pharmaceutical-industrial complex., Instead of simply empowering doctors to prevent disease, the Framingham study instead gave the super-organization of pharma, government, and the medical trade exactly the tools it needed to turn healthcare into a market, and clinical trials provided the tools to increase the scope of disease and grow prescriptions.

By 1961, the pharmaceutical industry understood that with a sufficiently broad definition of risk, they could begin to medicalize larger and larger populations, relatively healthy people who had yet to see themselves as patients. As one industry executive said that their goal for treating diabetes wasn’t to reduce its occurrence across the population but rather: “To uncover more hidden patients among the apparently healthy.” The Framingham study inspired the demand for still larger trials, needed to “render visible the relatively small improvements provided in less severe forms [of medical intervention].”

Risk factors thus became the tool used to uncover this new market of hidden patients. Instead of seeking ways to treat and cure symptoms of disease, pharmaceutical researchers were incentivized to hunt for precursors (surrogate endpoints), evidence that a patient could potentially develop disease and would need long-term (and preferably costly) intervention to prevent dying from it. In the discourse, this manifested as an upending of the dominant view of disease - instead of being seen as incurable spirals toward an eventual death, diseases were now seen as chronic conditions requiring surveillance, prediction, and management. But defining disease with these endpoints seemed a little… arbitrary.

A medical anthropologist, Joseph Dumit, puts it as such (quoting him at length):

“Illness was redefined by treatment as risk and health as risk reduction, and the line of treatment itself was determined by the clinical trial and an associated cost-benefit calculation. … If the RCT (randomized controlled trial) meant that doctors had to give up control during the trial and trust the numbers afterward, the emergent notion of illness as defined by that line was equally troubling precisely because it was both arbitrary and unsatisfying. Why at this number and not a bit higher or lower? Why are the numbers usually so round (everyone over 30 should be on cholesterol-lowering drugs?)”

The risk thresholds established for these diseases as a result of studies like Framingham did, as he says, have an arbitrary feel. There was no clear distinction in the risk factor between when a disease starts and when it ends, when one is safe and when one is at risk. In addition, since we’re dealing with statistical notions of health, not everyone at risk will actually develop the disease. So, what kind of a justification could we have for saying that all 29 year olds shouldn’t be on cholesterol-lowering drugs, but all 30 year olds should? Doctors, epidemiologists, and statisticians marshaled the facts to end this debate.

Geoffrey Rose, a pioneer of epidemiological medicine, was among the first to take this controversy head on. He posited first that the features discovered in the Framingham Study and in other epidemiological studies were diseases in and of themselves hitherto unrecognized in medicine, in which the defect is quantitative not qualitative. Let’s reiterate - the thresholds for disease identified by longitudinal epidemiological studies, are diseases themselves. In our study thus far, we have traced how the discourse of medicine socially shaped the notion of illness, from one of classification and genealogy, to one of interaction, etiology, and time-course, and now to one in the modern age where the presence of disease is purely statistical. In simplistic terms, one can think of the classificatory gaze and anatomo-clinical gaze developed by Foucault in Issue 3 as different versions of ‘what does he have, and does he have it?’. What we’ve developed here, which is a statistical-inferential gaze defined by epidemiology and clinical trials zooms right past this - everyone has it, it’s just about “how much of it does she have?”

Rose puts it as:

“this decision taking underlies the process we choose to call ‘diagnosis’, but what it really means is that we are diagnosing ‘a case for treatment’, and not a disease entity.”

The threshold becomes the diagnosis; the prescription for the diagnosis is chronic medicine. When the potentiality for death is made the disease, well, everyone’s got it.

Clinical Trials as Machinery for Generating Prescriptions

In Drugs for Life, Joseph Dumit, a medical anthropologist at UC Davis, presents a ethnomethodological and ethnographic study of how drugs are made in the US after World War 2. If you’re not familiar with these methods, it just means he followed pharmaceutical marketers and clinicians around for 15 years and observed how they think about, talk about, and perform their jobs, and, in turn, analyzed how these activities influenced their industry and overall medical knowledge. By the end of his extensive study, Dumit declares the hegemony of the clinical trial as the basis of modern medical research, that the guidelines from those trials have been used to change how we define illness from a set of symptoms doctors can treat to a set of risk factors doctors can manage. To aid in this chronic management of lifetime risk for death, a huge market for prescriptive therapy exploded into existence.

At the outset of a clinical trial, the research designers of the trial will choose a disease target, e.g. Alzheimer’s disease. Since companies eager for patents do not have the time to wait to see for certain if their drugs have an appreciable effect on disease progression ten years from now, they need a way to measure the therapeutic effect indirectly--and now--rather than ~10+ years down the line. So, rather than allow the treated and untreated disease run its course across a randomized sample of patients, what trial researchers do now is identify and choose a “surrogate endpoint”, something that reasonably lets them claim their drug regimen demonstrates some degree of efficacy in preventing the progression of the disease.

For example, instead of trying to treat the symptoms of debilitating Stage 7 Alzheimer’s disease, of which there are few surviving and able-bodied participants who can weather a 2-3 year trial, pharmaceutical marketers financing clinical trials will focus on earlier stage patients who exhibit much milder symptoms. There’s no a priori reason to assume that treating early-stage biomarkers of Alzheimer’s will actually manifest in less severe progression of Alzheimer’s, but this justification is never demanded up front from companies sponsoring studies by the FDA, or any other governing body.

Thus, it’s important to stress here that there are considerably more people experiencing mild to moderate symptoms of Alzheimer's than who will ever progress to Stage 7, with or without treatment. However, treating all patients with Alzheimer’s as potentially Stage 7 justifies early intervention and thus a new market for long-term drug intervention. You might think that the industry would go to greater lengths to obscure how its search for profit undermines health, but they’re actually quite brazen about it:

(click "display images" if you don't see anything here)

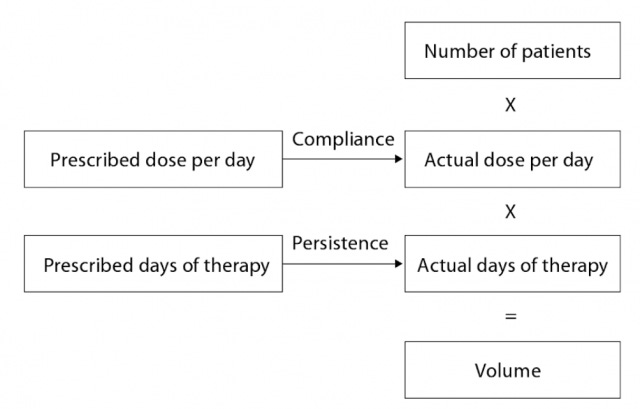

This figure is titled “Converting Patients to Volume”, from Forecasting for the Pharmaceutical Industry: Models for New Product and In-Market Forecasting and How to Use Them, and breaks down into objective categories, the various parts of the process entailing turning patients into revenue for a pharmaceutical company’s bottom line. Dumit examines the levers that manipulate each box in turn, but we’ll focus on just one - number needed to treat (NNT), which ladders up to the “Number of Patients” in the box above.

We’ve already seen how choosing a surrogate endpoint allows one to define a far larger market, because there will always be more people with a less severe version of an illness, but there’s always a tradeoff. Recall our discussion of risk factors above. Number needed to treat is defined as the number of people who need to be treated in order to observe the reduction of one adverse outcome, usually a death or a diagnosis of disease progression.

Put simply, let’s say you as a clinical trial designer treat one group of 100 people who have unknown likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s, and leave another group of 100 similar people untreated. You pick stage 6 -> stage 7 development of Alzheimer’s as your surrogate endpoint. Ten patients in the untreated control group develop Stage 7 Alzheimer’s compared to only 7 patients in the treatment group. Success! Your drug trial demonstrates 33.3% drop in the risk for progression (10-7/100). The number needed to treat to observe exactly 1 adverse event is [1 / (1-0.03)] = 33.3 people. These findings would indicate that your company would have to administer the pill to 33 people with unknown disease progression before you observe an effect of one less Alzheimer’s progression.

This would all be well and good in a vacuum, except that there is obvious capitalist pressure on corporate and corporately-funded trial designers maximize the NNT. Because drug profiteers can’t ethically give people diseases (yet), expanding the NNT is the only way to increase the total addressable market size for a disease..

So let’s say you, as a trial designer, like all of your colleagues, decide that you need to get a drug through a trial as quickly and cheaply as possible. You can’t afford to wait to see if you can reverse, revert, or inhibit progression of Alzheimer’s to stage 7. So you pick a surrogate endpoint somewhere at stage 2. You treat two groups of 100 people, same as above, but observe no effect in the treatment group. So you redo the study, theorizing that maybe the effect is perhaps too small to observe. You conduct the same drug intervention again, but with bigger groups of 1000 patients each. You now observe 10 progressions in the control group, 7 in the experimental. Success! What’s your NNT? Well, since you slapped a 0 on the end of the group sizes, it’s now 333. That’s great! You just multiplied the number of patients you can market your drug by a factor of ten!

Except that now, in material terms, you have to treat 300 more people than you did before in order to see get the same results - one less observed event. By definition, since you now have to treat more people to get the same effect, you have a less effective drug. Let’s repeat that so it is clear:

Pharmaceutical marketers, who control the design and output of clinical trials for the material gain of their companies, are under constant pressure to increase the total market size of a drug. Increasing the market size always carries with it the side effect of decreasing the effectiveness of the drug.

By choosing which trial to run (stage 2 vs. stage 6 Alzheimer’s, for example), the industry and its regulatory body increase the apparent illness that is treated, and arbitrarily expanding the definition of surplus health that is generated by the study.

Quoting Dumit:

“This is the public secret of capital-driven health research. Clinical trials can and are used to maximize the size of treatment populations, not the efficacy of the drug. By designing trials with this end in mind, companies explicitly generate the largest surplus population of people taking the drug without being helped by it. Since the trials are the major evidence for the treatment indication, which effectively becomes the definition of the illness or risk, there is a rarely any outside place from which to critique or even notice this bias.”

By utilizing the risk factor, deploying it in NNT calculations in order to define markets, and running clinical trials to move those markets, the pharma-industrial complex in concert with clinicians has completed the transition from genealogies of health (classification) and empirical practice (anatomy and clinical experience), to mathematical subjugation and control (statistical-inferential gaze). It's not clear that medicine has ever really worked well, but it's clear now that the introduction of capitalist bias in the discipline of fact discovery has completely warped our notion of care at the expense of understanding our actual physiology and the ways in which drug interventions actually affect the body.

As Dumit says, clinical trials are being designed in order to answer the question of “What is the largest, safest, and most profitable market that can be produced?” The question is not one of choices by designers, but one of structural pressure and violence. As a result, many clinicians, patients, and even pharmaceutical analysts can no longer imagine how to generate accurate clinical information about the body. We have been alienated from our subjective physiology by medical facts.

What would the world look like if Dumit is in fact correct about the structure that produces medicine and medical facts? What would we expect to see if these critiques are true?

Novartis just last week joined other pharmaceutical companies in ending their antibiotic research programs. Staph and MRSA infections have been identified by the CDC as a leading cause of death during hospitalization, if not the leading cause. Staph infection is not something that can be managed chronically, however. It’s episodic. The majority of people, if they are not wont to hospitalization, are not at a quantifiable risk of getting staph. Since they’re not, it makes no sense for antibiotic research programs to exist - and now they don’t!

You’d also probably expect to see more of this risk language proliferating amongst the general public, with more and more language addressing chronic management of symptoms. Maybe your direct-to-consumer advertising would frame all diseases as chronic, embedding the management of risk directly in the ads.

Perhaps they’d look a little something like this:

Figure credit: Drugs for Life, Joseph Dumit, 2003. (click "display images" if you don't see anything here)

In the next issue, we’ll finally tie this all together with the history of SSRI drugs, the medicalization of depression, and the production of the first SSRIs. We’ll see how serotonin's receptor transmission targets were identified for surrogate endpoints incorrectly, how serotonin transmission was objectified into various categories against these endpoints, and how 3 generations of drugs were engineered for these endpoints with the machinery of thresholds derived from standardized questionnaires (PHQ-2 and PHQ-9), so that larger and larger populations of people could be targeted for medicalized depression treatment.

Thanks for subscribing! If you would like to share this newsletter with anyone, you can suggest they sign up here.

Dumit, Joseph. Drugs for Life: How Pharmaceutical Companies Define Our Health. Duke University Press, 2012.

Greene JA. Prescribing by Numbers: Drugs and the Definition of Disease. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.

Pickering, GW. High Blood Pressure. 2nd ed. J. & A. Churchill, Ltd, London; 1968.

Rose, Geoffrey. Rose’s Strategy of Preventive Medicine. OUP Oxford, 2008.

“Converting Patients to Volume,” Cook 2006.

Bartfai, Tamas. Future of Drug Discovery: Who Decides Which Diseases to Treat? Elsevier Science & Technology Books, 2013.

Bloomberg.com. (2018). Novartis Exits Antibiotics Research, Cuts 140 Jobs in Bay Area. [online] Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/amp/news/articles/2018-07-11/novartis-exits-antibiotics-research-cuts-140-jobs-in-bay-area [Accessed 14 Jul. 2018].

Klein E, Smith DL, Laxminarayan R. Hospitalizations and Deaths Caused by Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus, United States, 1999–2005. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007;13(12):1840-1846. doi:10.3201/eid1312.070629.